Older man=sugar daddy, older woman=cougar. Hmph. Paula Coston is confused

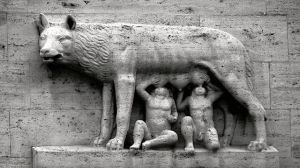

The myth of the feral bitch nurturing the boy baby: is ‘cougar’ partly about that? Capitoline wolf nurses Romulus and Remus. Image courtesy of CellarDoor85

Hello, George Sand, wherever in heaven you are now. This week I bow, blogwise, to you. You were the cougar to the much younger Frederic Chopin. Your pairing ran like a thread through both your creativities.

I’ve been a cougar in my time, by which I mean, in some phases of my life I’ve felt especially attracted to, sought out, younger men. I wanted them to look noticeably younger, too. I don’t think it was a way of winning other women’s admiration, or anything like that: I was just attracted to their (adult) boyish faces and reed-like physiques. I seem to have grown out of it, though. A year ago, on holiday in Sweden, a handsome, reed-like thirty-year-old approached me (58) and I instinctively rejected him outright.

One theory for women’s cougar behaviour (although not all scientists even believe it exists) is that it may emerge, or peak, when their fertility hasn’t long to go: that at that time, they may instinctively seek out younger men as likely to be more fertile themselves, to up their chances of conceiving, before it gets too late. I don’t believe that that applies to me: I’ve had peaks and troughs in my cougar desires, which first featured in my twenties, and last reappeared when I was years through the menopause and out on the other side. Whatever the reason, though, I do suspect that I’ve now lost it forever. These days, for me it just feels wrong.

So is cougar behaviour wrong in principle? I can’t think why it should be. Yet how society views it – and the term ‘cougar’ itself – is far from consistent, and, over time, has changed.

The idea of the human female cougar seems to have popped up in 1999, when two Canadian women founded a dating website, Cougardate.com, to match up older women with younger men. But already there’s contradiction in the name’s associations, because this story heads off along at least two separate tracks. Track a) suggests that one of the site’s founders took the name from her nephew’s description of such women as cougars in search of small defenceless animals. Track b) relates that it came from a phrase used by his fellow hockey players. (Or was it supposed to have been the actual name of a team? There’s certainly a women’s hockey team at the University of Regina with that moniker.) Already, a veil of mythology begins to fall.

Modern history continues. In 2003, the American Association of Retired Persons revealed, from a survey, that an unexpected 34% of 40+ women were dating younger men, and 35% of them said that they preferred to. In 2001, a Toronto Sun columnist propagated the term by publishing a book, Cougar: A Guide for Older Women Dating Younger Men, in which she defined this female as a 40-plus-year-old who wanted ‘younger men and lots of great sex’ and rejected ‘children, cohabitation and commitment’. Courteney Cox then carried on the cougar baton in the sitcom Cougar Town , helped by a TV reality show, The Cougar, of 2009, which involved a 40-year-old woman choosing a boyfriend from twenty men in their 20s. So far, so joky-stroke-semi-serious.

But then, there was a backlash – or more, a subtle and progressive backstroke – in attitudes from some quarters. In 2010, Google banned the dating site Cougar Life (while retaining plenty of male, i.e. ‘sugar daddy’, sites), and Carnival Cruise Lines dropped its second annual Cougar Cruise for older single women and younger single men. What had seemed like a harmless, even flattering, name for some of us suddenly became unwelcome. For that reason, maybe, it seems less used these days.

Real cougars, in the wild, are the largest of the small cats; they’re quite solitary; and they hunt small rodents, even insects. There are definite connotations of threat and predation about real cougars.

Yet older men are not usually painted as sexual ‘predators’ unless they target females who are actually underage. ‘Sugar daddy’ is a blatant euphemism,though, is it not? Pretending to be harmless and fluffy, hiding something worse. What lies behind the phrase is an imbalance of power based on money and status. Yet no tint of menace has fallen, given time, over the phrase.

Nature, when associated with human sexuality, often gives language a sinister cast. Cougars are all teeth and fur and claws, incongruous and bestial features in a woman. Paedophiles and pursuers of the very young are said to ‘groom’ them, as if taming, as much as wildness, is a bad thing. The term ‘foxy’, used of women, feels double-edged.

In the story of Little Red Riding Hood, the wolf dresses up as the grandmother, merging images of uncontrolled beastliness and the older woman in the bed, the place where sex often happens. A terrifying scenario to confront an innocent child with. In Tea Obreht’s recent novel The Tiger’s Wife, a young village woman becomes associated, married, with the myth of a roaming tiger. In the minds of the reader and the locals, the two figures merge. There’s an implicit suspicion that they are in some sense coupled and have sexual relations, and as a result are feared and avoided.

Where do all these hidden repulsions stem from, if they don’t come into play with the male equivalent? One theory runs that the older woman-younger man image drags up the incest taboo (fear of the so-called Jocasta complex): associations of ‘family’ from seeing an older woman and a young man together. But then, why doesn’t that apply to an older man and a younger woman, i.e. the other way round? Another theory runs that there feels to us something subconsciously wrong with a pairing of ‘unequal’ desirability levels – unless the woman neutralises this sense by being exceptionally attractive, in men’s eyes. Scientists seem to mean by this that couples expect their desirability levels to seem similar because that also signals, to the primitive in all of us, similar levels of fertility and ‘breedability’.

Another source of revulsion at the cougar image may be real stories of wild animals snatching or mothering children. I remember the case of a dingo stealing Azaria Chamberlain’s baby near the mythological icon of Ayers Rock. Online, you can access a list of all the children and babies taken or mauled by cougars in North America. You well might wonder, why? The tale of Romulus and Remus is probably a fable, but in 2001, a 10-year-old Chilean boy was found to have been living in a cave with a pack of dogs for at least two years, possibly fed from the teats of one of the bitches, and in 2008, a one-year-old boy was found being protected, cleaned and kept warm by feral cats on the streets of Misiones, Argentina. There are other real life tales, some of them about girls, but it’s the cross-gender pairings, animal mother with boy infant, that seem to make people shudder more. Maybe it’s something to do with the image we get of suckling; maybe that does conjure up a sexual image of boy on woman that part of society dislikes.

There are myths that may taint the cougar image further. Korean legend has a kumiho, a beautiful but malevolent young woman who can shapeshift into a fox; she uses her beauty to seduce men, eating their hearts or livers in an effort to become human. Scandinavian legend tells of the Maras, a race of she-werewolves who endure slow, agonised transformations in the night. In Japanese folklore, Bakeneko, spiritual beings a bit like foxes or racoons, menace sleeping humans, even killing or consuming them, and sometimes morph into beautiful girls.

The toxic taste endures in more contemporary culture. Val Lewton’s 1942 film Cat People, which has been re-made since, features female shape changers with a feline alias. In the more recent She-Ra: Princess of Power, the villainess Catra can change into a panther.

All this baggage seems to leave the sexual term ‘cougar’ weighed down with a primeval sense of danger, even repugnance, despite its lighthearted beginnings. As for ‘sugar daddy’ – well, it still sounds fluffy. Doesn’t the imbalance seem unfair?

It is the “battle of the sexes” going on; nothing more, nothing less. However, women are still at a disadvantage because the society itself is still male oriented.